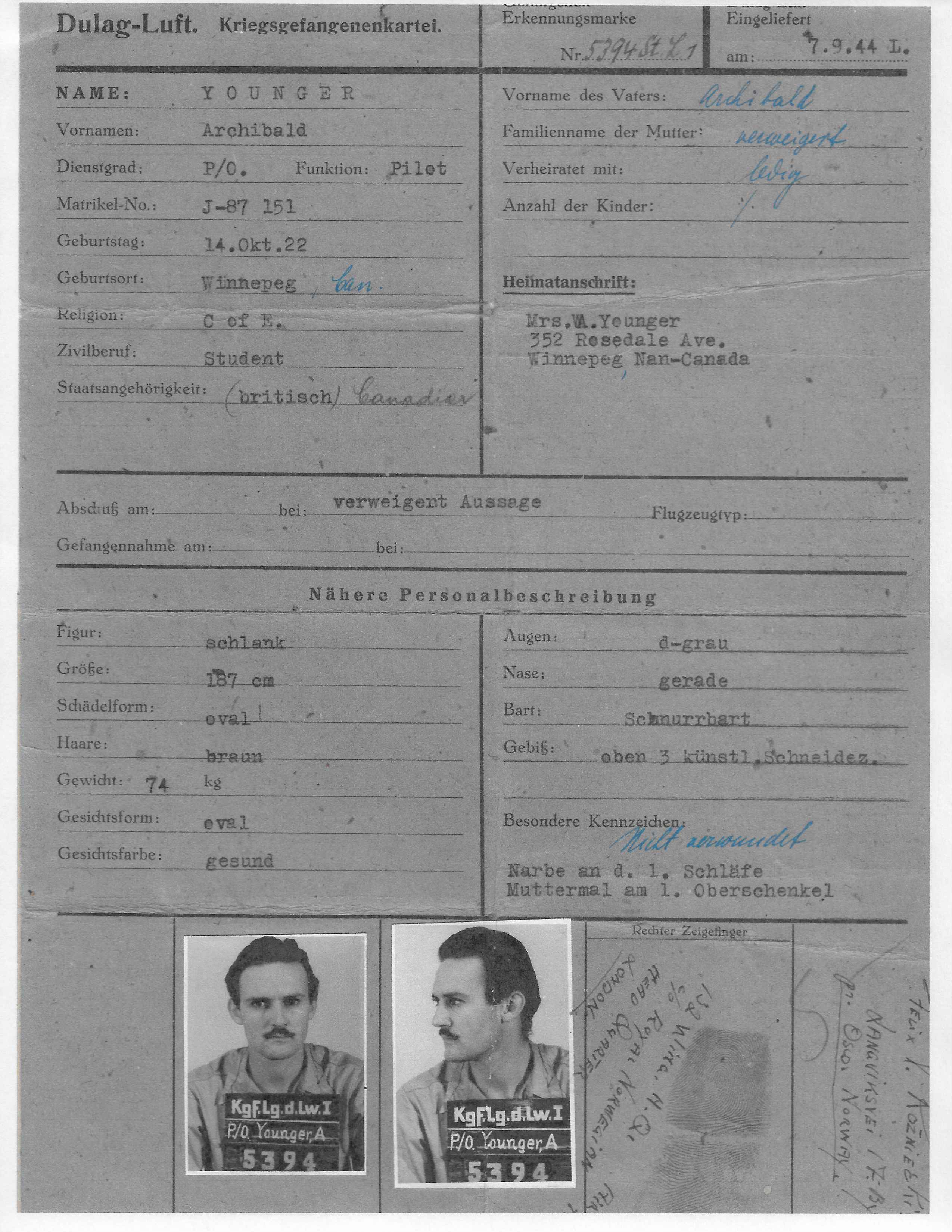

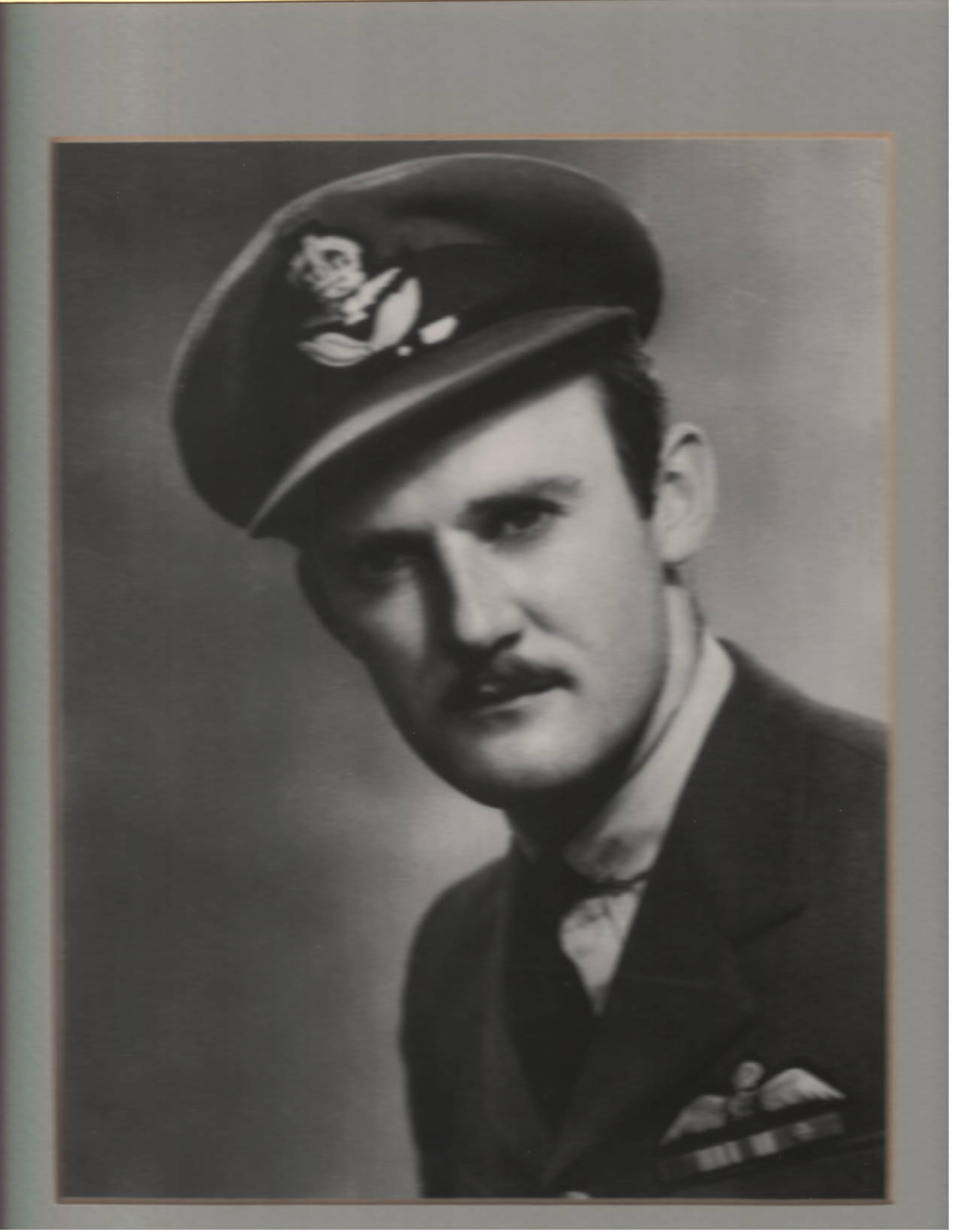

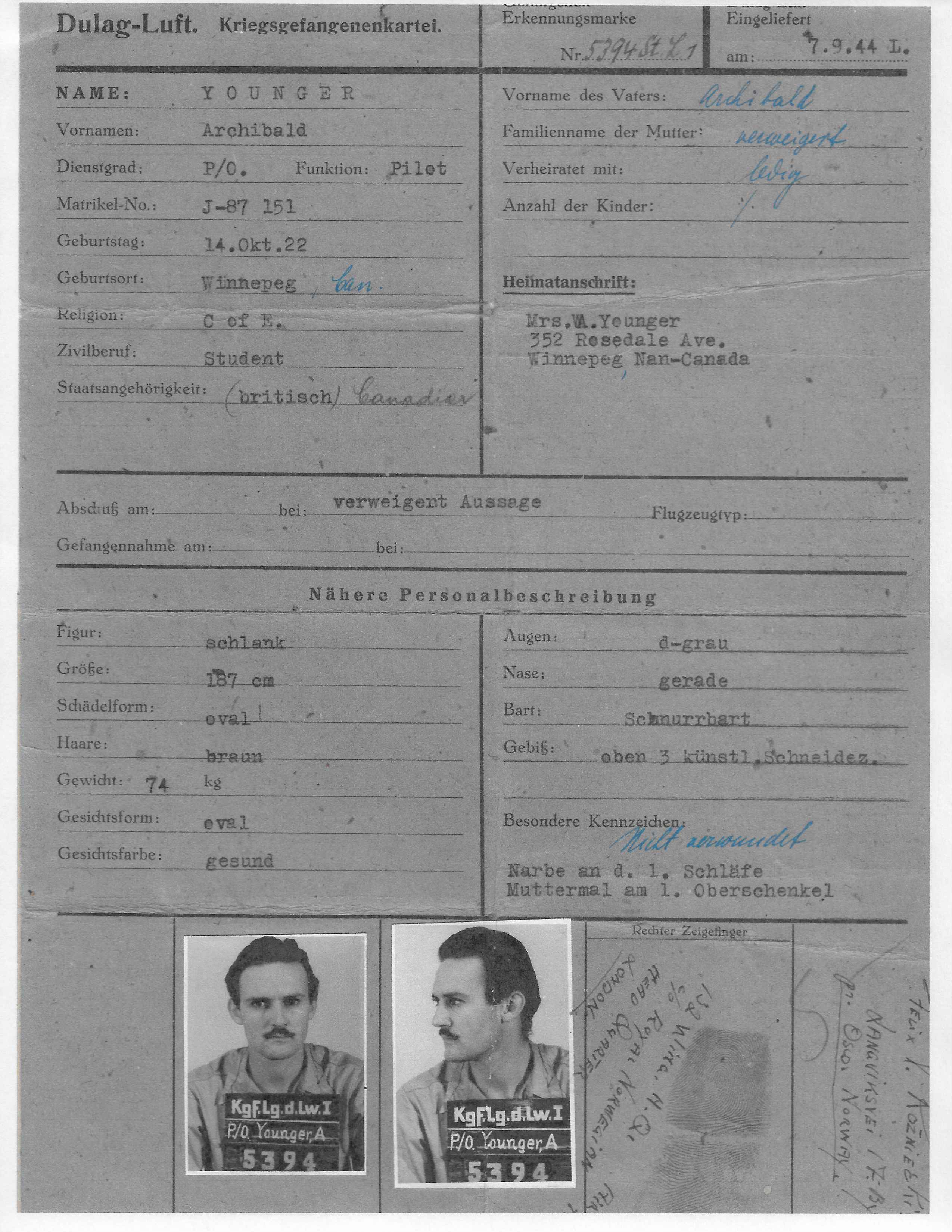

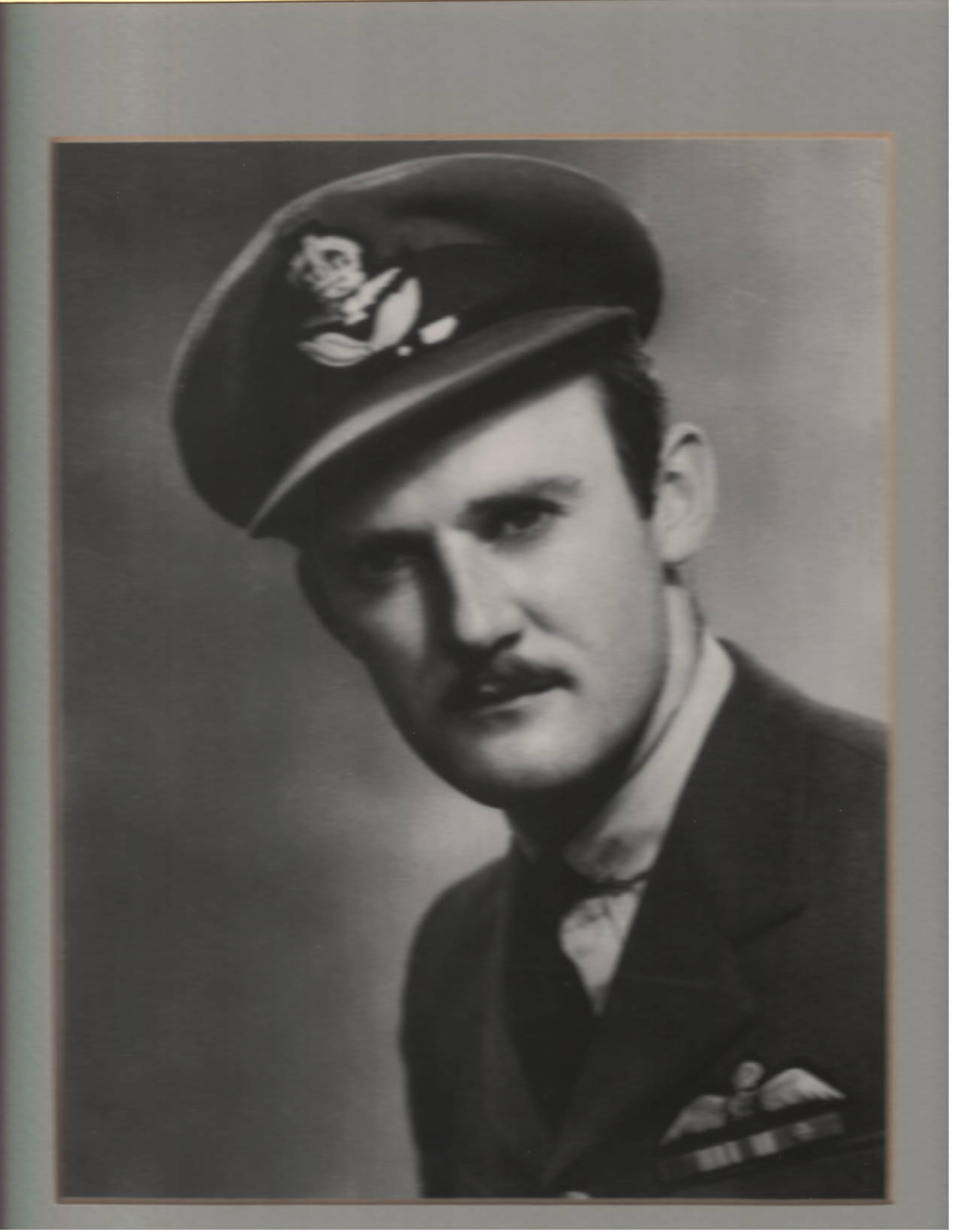

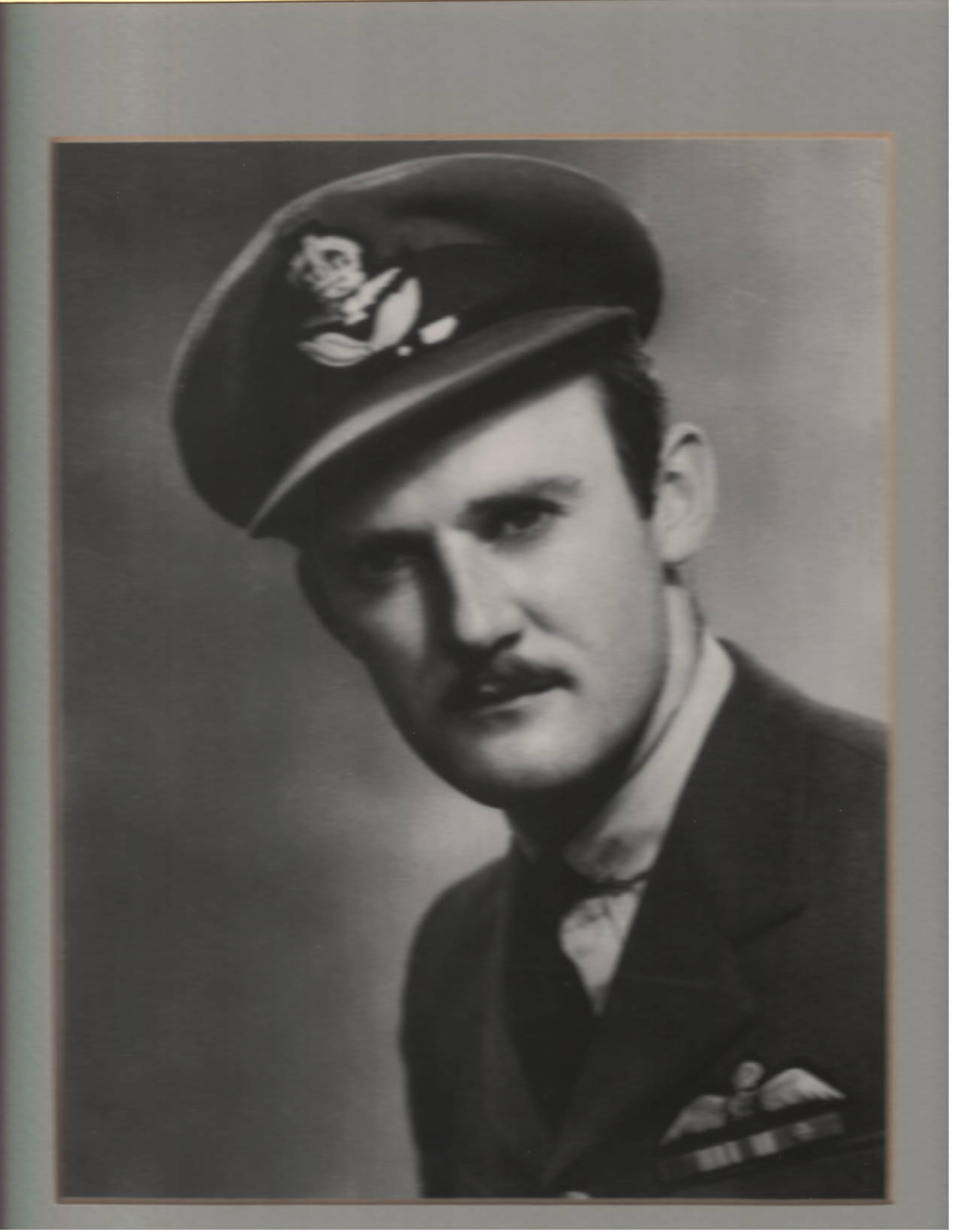

Archibald Younger

October 14, 1922 - June 10, 2005

247 Squadron

Art's story is courtesy of his son, Ryan, through photos and documents, articles and Art's diary.

Archie was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

He completed Grade 11 in 1940.

Art's Journey Through the BCATP to the RCAF and RAF:>

- January 1941: Joined RCAF, sent to Manning Depot, Toronto.

- ITS: Victoriaville, Quebec

- EFTS: Trois-Rivières, Quebec

- SFTS: Summerville, PEI. Received his Pilot's Wings November 1941.

- Boarded Letitia, December 13, 1941, in Halifax, NS.Moved out into the harbour until December 15.

- Set sail for England on December 16, 1941. Thirteen ships in the convoy. Twelve days' voyage.

- Arrived in Liverpool December 25, 1941. Remained on ship for Christmas, with menu of stew and bully beef.

- Departed for Bournemouth on December 26, 1941 and billeted in hotels pending draft to O.T.U.

- Drafted for Middle East, December 31, 1941. Sent to Padgate (RAF Pool near Manchester).

- Travelled north by train through England and Scotland to Scapa Flow, then boarded "Viceroy of India" on January 6-7, 1942. Six men to a cabin. Poor food.

- Sailed for India, with 28 ships in a convoy, January 8-9, 1942.

- Arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone for refuelling and stores, January 25, 1942. Not allowed to go ashore.

- Sailed from Freetown, now 18 ships in the convoy, January 29, 1942, down the coast of Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope to Durban.

- Reassigned to Middle East as Singapore had falled to the Japanese. Sent up the Red Sea to the Suez. Tent Camp at Kasfareet, Egypt. Had a short tour in Libya by truck. Boarded Egyptian riverboat up the Nile as far as the Aswan Dam, then by train to Khartoum, Sudan. Flew from there to Asara, Eritrea. Archie said, "Rommel was sweeping across the desert -- Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, hoping to reach Cairo. Then if he could take Malta, he would control the Mediterranean. We manned anti-aircraft guns -- repaired and tested damaged aircraft. Rommel was stopped at El Alamein so we were reassigned to return to England. We flew from Eritrea to Khartoum by train, back to the Aswan Dam," taking the reverse route back to Suez. "We boarded a warship through the Suez Canal down the east coast of Africa to Durban, where we stayed for several weeks awaiting another ship. When it arried, we proceeded to Capetown, where we spent some time ashore, then sailed for Britain."

- Advanced Training Unit at Watton, Norfolk, England, flying the Miles Master II, between January to May 1943.

- #56 O.T.U. at Tealing, Scotland, flying Hurricane, from May to July 1943.

- Joined 186 Squadron, October 1943 staying until February 1944, in Ayr, Scotland, flying the Hurricane IV. Converted to Typhoons November 1943. 186 Squadron disbanded with all pilots posted to various Squadrons in 2nd TAF in the south of England: 181, 182, 183, 245, and 247, converting to rocket Typhoons.

- Joined 247 Squadron (China, British) at Merston. Sent to Hurn Aerodrome near Bournemouth, attacking V1 sites, trains, radar sites on the French Coast, prior to the Invasion.

- Operated out of the beachhead in Normandy (B6 Coulombes), June 1944, with 69 rocket attack operations, V1 sites, fighter sweeps, pre-invasion radar sites, and close support for the Army.

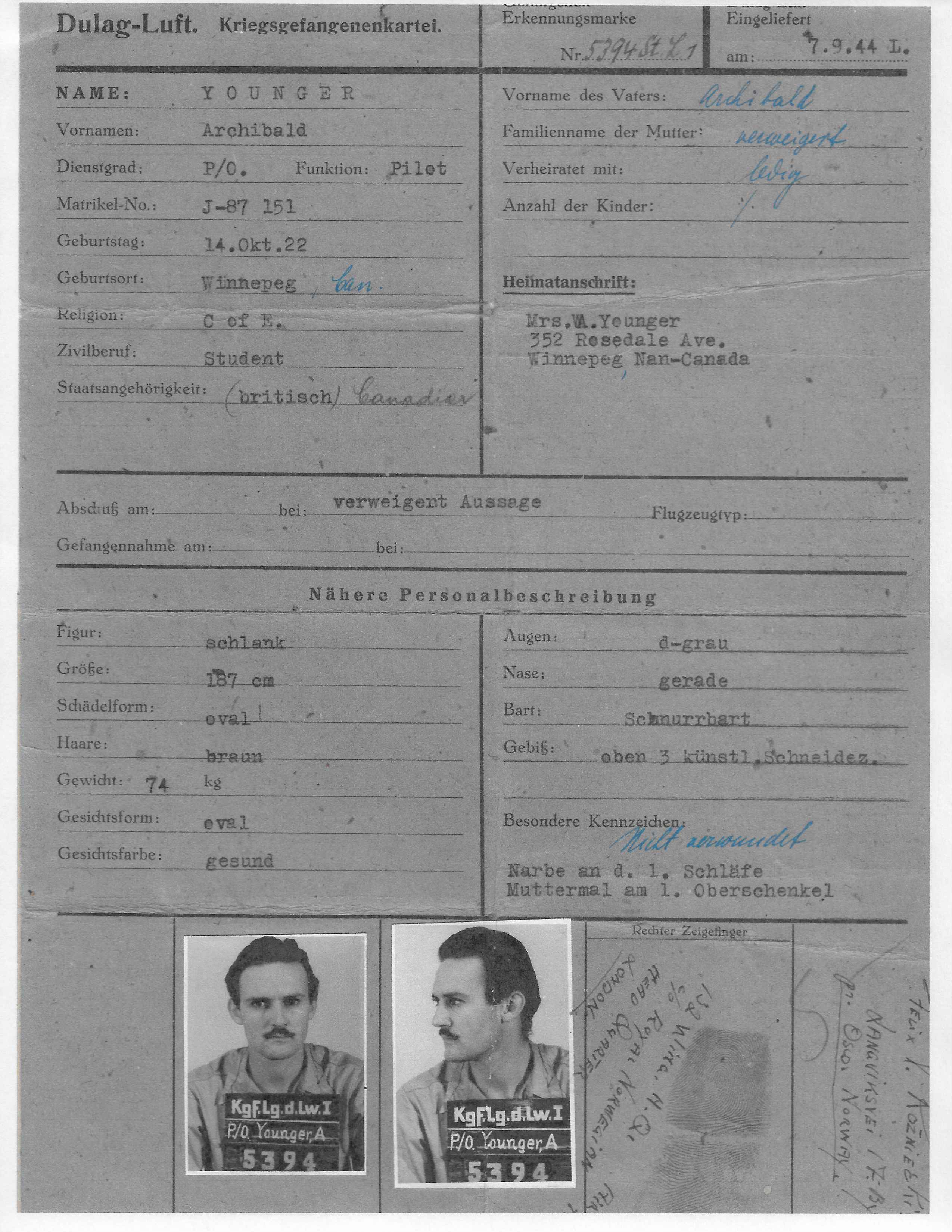

- Shot down at Falaise Gap on August 13, 1944, low-level tank busting. Archie said, "I was shot down by light flak, 20 mm, I think. Fortunately, I had enough altitude to bail out, and came down in a forested area. Despite the fact that there were Germans all over the place, I managed to evade capture for two days, but my luck ran out when I was attempting to get down to a river for water. I had been avoiding patrols with no difficulty because of lots of cover, and I had observed this patrol of seven Krauts approaching. I was well hidden in a ditch and smugly laughing, when they decided to cross the ditch right where I was lying, so it was game over. Fortunately, they were Wermacht and not S.S. I was subsequently turned over to a Luftwaffe Officer and a couple of NCO's. They had a vehicle and were trying to make their way out of the Falaise Pocket, along with the remnants of two German Armies, namely the Fifth Panzer Army and the Seventh Wermacht Army. The slaughter was unbelievable -- mile after mile of burnt out tanks, half tracks, trucks, and horse-drawn equipment. Cows, horses, and human bodies were all over the place. The fighter bombers were ranging all over the area, and in particular, the Typhoons with their rockets and cannon. Typhoon pilots who were flying over the Pocket a few days later told me that the stench at 5,000 feet was nauseating and overpowering. You have to be on the receiving end of a Typhoon attack down a congested road with vehicles bumper to bumper to appreciate the lethal capacity of these aircraft. The rockets are terrifying, and the cannon fire is murderous. The majority of the Germans trying to flee the Pocket were survivors of the their units, and were in very tough shape, and mostly in bad shock from the hammering. Three Luftwaffe types and myself were joined by a South African Typhoon pilot who had been shot down in the middle of this charnel house. He was wounded in the back and legs, and had lost his flying boots when he bailed out, so he was barefoot. The Oberleutenant warned us not to try escaping, because the place was crawling with the S.S. troops and our chances would be nil. As a matter of interest, this officer had worked at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto, speaking English fluently. We continued on with our vehicle towards Trun and the Corridor of Death making detours as required. There were whole convoys of Red Cross ambulances shot up and burnt out on the sides of the roads. Finally, we were stopped by an S.S. Hauptman, and when he found out we were Typhoon pilots, he asked us what kind of animals were flying those aircraft that would shoot up an ambulance. The South African told him in no uncertain terms that the ambulances coming into the Pocket were carrying jerry cans of petrol and ammunition in and wounded out, and that's why they were being shot up. The S.S. Officer was working himself up into a rage, and he finally said, 'I will stop the next ambulance coming in, and if they don't have petrol cans in the back, I am going to shoot you two.' We did not have long to wait, and the next small convoy of ambulances arrived shortly, and upon inspection, proved to be carryig petrol. We hustled the South African into the vehicle and with the Luftwaffe personnel shaking their heads, we took off at the first opportunity and finally made it out of the Gap on the 15th or 16th of August. The following day, we reached a POW holding area at a school yard, where we joined American and British POWs. My recollection as to numbers is vague, but there were hundreds (infantry, tank crews, aircrew, etc.). The march then started, including the walking wounded. The word quickly went down the line. 'Keep walking or you're dead.' The Germans did not leave any prisoners behind, even when they had to leave their own men, as was evidenced when we crossed the Seine River west of Paris by small boats. The French villagers were well aware that the Germans would shoot stragglers, so they took turns following the column with their horse drawn carts, and as the boys collapsed or passed out, they threw the up on the cart until they revived. At the next village, another farmer would take over and follow the column until he was relieved further down the road. The retreat continued on foot and by truck and freight train when available. The route followed was to Amiens, Nancy, Metz, Frankfurt, Berlin, and then to Stalag Luft #1 at Barth, Pomerania on the Baltic Sea. The trip took 30 days." Archie explained some of the experiences. "We were billeted in one of the local prisons and observed the brutal treatent handed out to political prisoners. Most of the nights were spent in freight train marshalling yards and as we were 40 men to a boxcar, living conditions were grim. Ventilation consisted of 2-four feet square (16 square feet) windows blocked with barbed wire, and the bathroom, or lavatory, consisted of three buckets. When the buckets got full, they were emptied through the barbed wire. Needless to say, most of the chaps abstained as long as possible, and when the train stopped, upon the sliding doors being opened by the guards, a made rush ensued to the nearest ditch. When we finally arrived at Dulag Luft (Frankfurt), it was the first proper prison we had been in. This was the Interrogation Centre for all captured aircrew, and their first move was to put you in into solitary to soften you up for questioning. The interrogation did not amount to much because the Gerans knew by then there was no fresh information to be had and that their defeat was inevitable. It was a relief to get some half-decent food again, because on the journey, we had existed on black bread, raw vegetables and water. It was easy to tell when one of the chaps had just come out of solitary because they would not stop talking. You would just let them babble on. Some of our chaps, while exercising in the compound, threw black bread (our saviour) over the barbed wire to civilians, and it was really appreciated." Another set of stories: "Inevitably, after lights were out and we were all in our bunks, a lot of conversation ensued. We did our own cooking in each room on a peat or coal stove. We worked in pairs and my partner was John Stoyko of Ituna, Saskatchewan. The rest of the chaps constantly complained that John was always smoking when he was cooking, resulting in ashes in the soup. John insisted the cigarette ash gave the soup more body. Life in Stalag Luft 1 was characterized by boredom and hunger. However, the Red Cross sent food parcels and sports equipment, so that we could play baseball and soccer. A lot of bridge and various card games were played and in lieu of currency, we used cigarettes. We were subsequently liberated by Russian Mongolian Cossacks during May 1945. There were 10,000 Allied aircrew in Stalag Luft #1, and they were repatriated by air to the UK in three days.

- Art's nickname was Razor.

After the war, Art worked as a log scaler in British Columbia. In 1957, he joined BC Log Spill, where he became general manager. In 1973, he became an independent marine surveyour, specializing in log spills, remaining active in this capacity into his mid-70s.

Art was married to Florence 'Alma' Buckingham on February 15, 1952 in Admiral, Saskatchewan. Together they had a daughter and a son, plus four grandchildren.

LINKS: