Unknown - May 5, 2007

Anthony Frombola/Frombolo was born in Oakland, California, the only son of Peter and Bianca Frombolo. He graduated from Alameda High School and worked briefly on oil tankers for Standard Oil, then attended the University of Oregon.

When the Second World War broke out, Tony joined the RCAF in 1940 and flew almost 70 operations as a fighter pilot with 440 Squadron before being shot down and becoming a prisoner of war for seven months in a German prison camp. He was released from the RCAF on November 11, 1945.

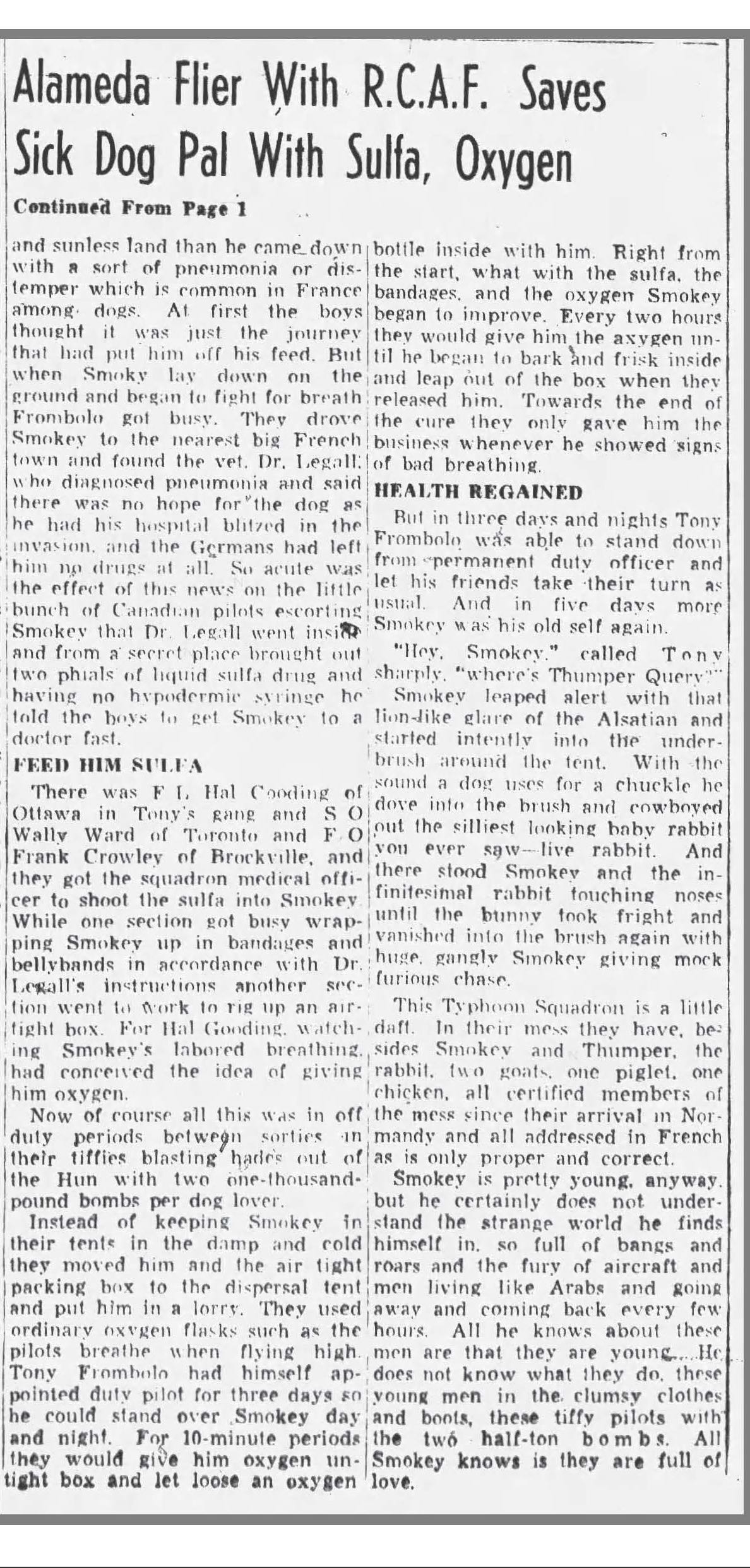

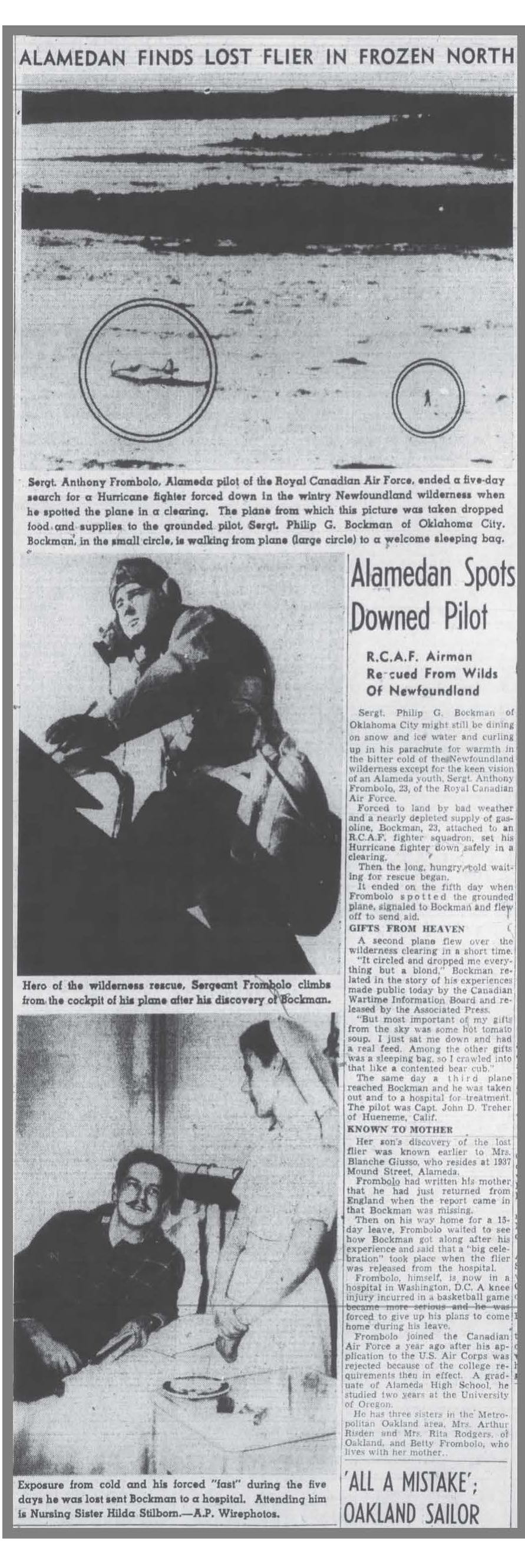

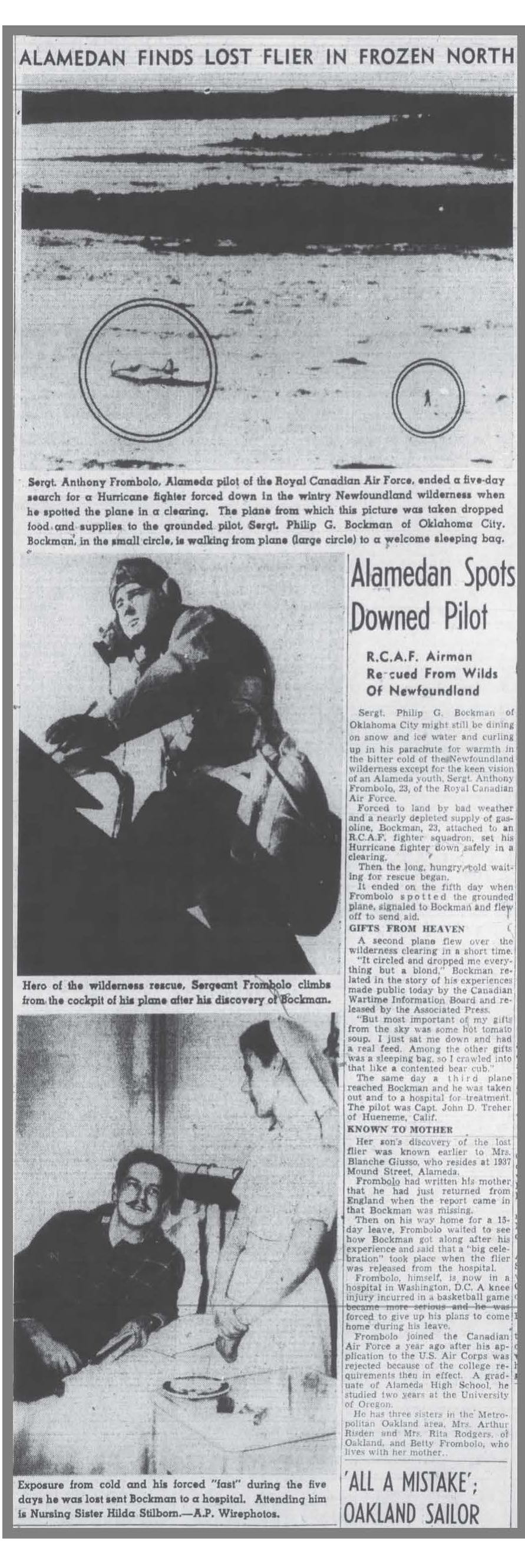

He got his wings at 2 SFTS in Uplands. Course 51: 14 March – 3 July 1942 (Sgt pilot). He flew Hurricanes with 127 Sqn RCAF until Dec 43 when the unit went overseas and became 443 Sqn, “possibly” doing a stint at 1 OTU in Bagotville in late 1942 before going to 127. He was definitely at 127 Sqn in December 1942 (see 2 attached photos). His NCO SN was R122110. He was commissioned in July 1943 Sgt to P/O receiving the SN J28761. He joined 440 Sqn on 26 May 1944. (Most 127 squadron personnel arrived in the UK in early to mid February 1944, he joined 440 sqn in May. This is pretty much the time frame he would’ve required to go through an OTU, 3 TEU and 83 GSU, the normal chronology for a pilot at that time.) PL-14148 16 December 1942 # 127 Fighter , Gander Sgt. Anthony Frombolo of Oakland, Calif., carries a map with him as he climbs into the cockpit. Fighter pilots spread maps on their knees, must be expert navigators. PL-14154 16 December 1942 # 127 Fighter , Gander This is Sergeant Anthony "Tony" Frombolo of Oakland, Calif., one of eight U.S. pilots in the squadron.

From an RCAF Press Release dated May 23, 1945: "Germans behind the Russian lines were so stricken with abject terror that British and American war prisoners regarded them with pity in spite of the harsh treatment they had themselves received during their confinement. So complete was the morale collapse that many Russian soldiers did not carry ammunition for their weapons -- they didn't need to. This was reported today by two Typhoon pilots who walked to this airfield from Stalag Luft One, at Barth, Pomerania, a distance of about 250 kilometres of which 100 were through enemy territory. They believed the terror was inspired by two things: guilty knowledge of the German atrocities in the Ukraine and indirectly the result of the intense propaganda by which the Nazi government hoped to spur resistance during the siege of Berlin. The pilots were F/O Anthony Frombolo, Alameda, California, a member of the City of Ottawa fighter-bomber squadron with this Canadian wing and William Smiley, Perth, Ontario, a member of a sister RAF Typhoon wing. Frombolo was shot down while attacking railway lines near Wesel on November 28, 1944 and has been in Stalag Luft One since December 23. Smiley was badly beaten, and lay bound and bruised for 20 days in a railway boxcar at Dortrecht for attempting to escape. He was shot down on Friday, October 13, over northern Holland, and was three weeks being moved to a prison camp. Frombolo narrowly escaped death when he was shot down. His Typhoon caught fire 20 miles behind enemy lines from a direct hit. He attempted to reach the front, losing altitude. At 1,500 feet, he jumped after seeing 20 mm cannon fire spurting through his wings. The left heel of his flying boot was shot off, so were his goggles. He heard the Typhoon crash before he pulled the ripcord, and was captured two hours after he hid in a muddle when a Wehrmacht soldier stumbled over him. The young German soldier was assigned by his older companions to march Frombolo to an advance post. On the march back, he commenced screaming that his father, mother, and sisters had been killed by Allied bombers and obviously considered shooting his prisoner, but Frombolo persuaded him to take him to his commandant. There were about 8000 prisoners, mostly Air Force, at Stalag Luft One when they first arrived. As other camps were overrun, the Germans brought in more prisoners until 10,000 were here when the guards bolted on April 30. British and American military policemen took charge until the Russians rolled up on May 2nd."

In another press release dated May 23, 1945: "Flying Officer Anthony Frombolo took a street car into captivity after his Typhoon fighter-bomber was shot down near Wesel on November 28th. His aircraft was literally shot to pieces and he was captured when he parachuted from 1500 feet. With 20 English soldiers, the RCAF pilot spent the first night in the village of Wetting under guard. The next day, the party marched to an Army prison camp and he was turned over to two elderly guards who were to take him to an interrogation centre. He recalled, "The three of us marched into Krefeld and waited for a streetcar. I got on and walked down the aisle and sat down. One of the guards sat across the aisle from me. There was a civilian in front. The other guard was at the back of the street car, paying the fare for us. We got to the other side of Krefeld and transferred to Dusseldorf. It started to rain. I was chilled and as we walked, the water squelched in my flying boots, but it was so funny, I laughed. It got so dark that if I had sat on the sidewalk, the guards would never have found me. Several streetcars passed. One stopped, but wouldn't let us on -- too crowded. Then the guards tried to stop some trucks. For two hours, they would stand in front of each vehicle with their rifles in front of them shouting, 'Halte' but the drivers swished right past them. They muttered 'dumkoft' and tried again. We finally got on the back of one and got into Dusseldorf. Then the air raid sirens started. I heard Mosquitos above the low ceiling droning round and round. We marked into an air raid shelter for about two hours, then we marched out to a beer parlour. One guard bought three beers and the other gave me a cigarette. Then we got on the train for Frankfurt. We stopped every time there was an air raid. Nobody seemed the slightest bit interested in us. That journey should have taken 12 hours but it took 23. I saw there was nobody on the opposite seat with one guard and asked him to change with me so I could lie down. He muttered, 'ja' and came over. They had given me half a loaf of bread so I sued it for a pillow and went to sleep. I woke up the next morning and the two guards shared their rations with me. When we got into Frankfurt, we took a streetcar to the interrogation centre. Then I went into solitary confinement and had two chunks of bread each day and a bowl of watery soup. I had one blanket, heat was on two hours at night before we went to bed and I'd wake up at 1 am regularly with the cold. They took our boots each night so we couldn't walk the three paces one way and two the other to keep warm. There were two signs on the walls. One said, 'Tampering with the radiator will result in no heat for anyone' and the other said ' Marking the walls will be severely punished'. Everybody who'd been in there, I guess, had made a scratch on the wall to keep track of the days. There were lots of scratches. The average time seemed to be 10 to 12 days in solitary. If you were in bad shape when you were put in there, I guess you'd go crackers. I'd have been banging my head on the walls in another couple of days but they transferred me to the camp at Barth, Pomerania."

After a short tour with the US Air Force Reserves, he went into the restaurant business. He also worked at Airmotive Industries, and then retired to play golf and do some travelling.

He was married to Margorite and then Dorothy, who both predeceased him. He had three children and six grandchildren, with nine great-grandchildren. He passed away on May 5, 2007 in Rancho Mirage, California.

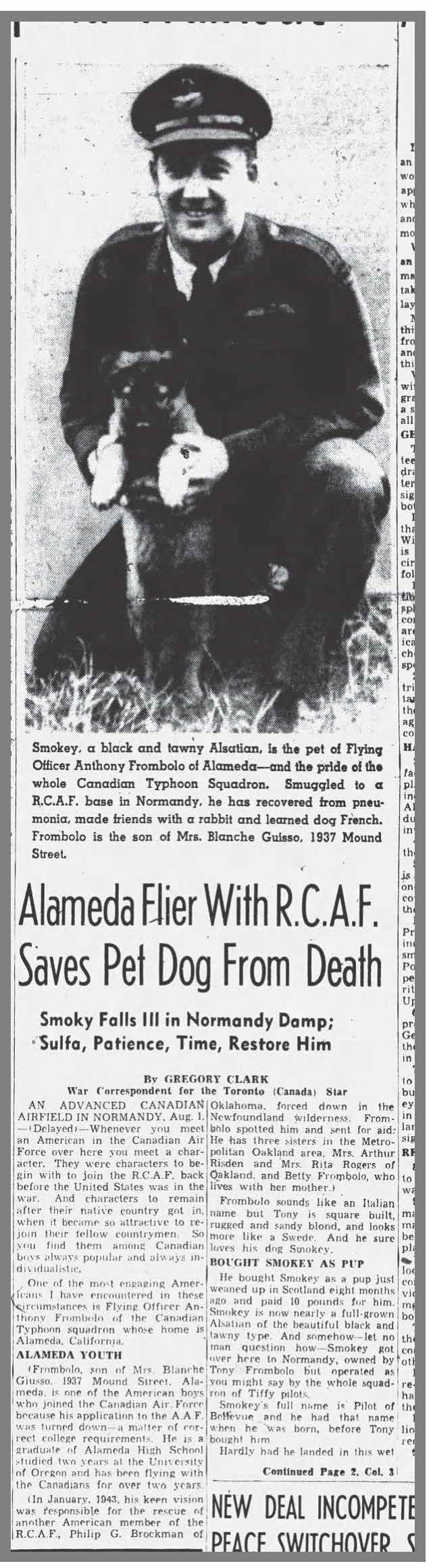

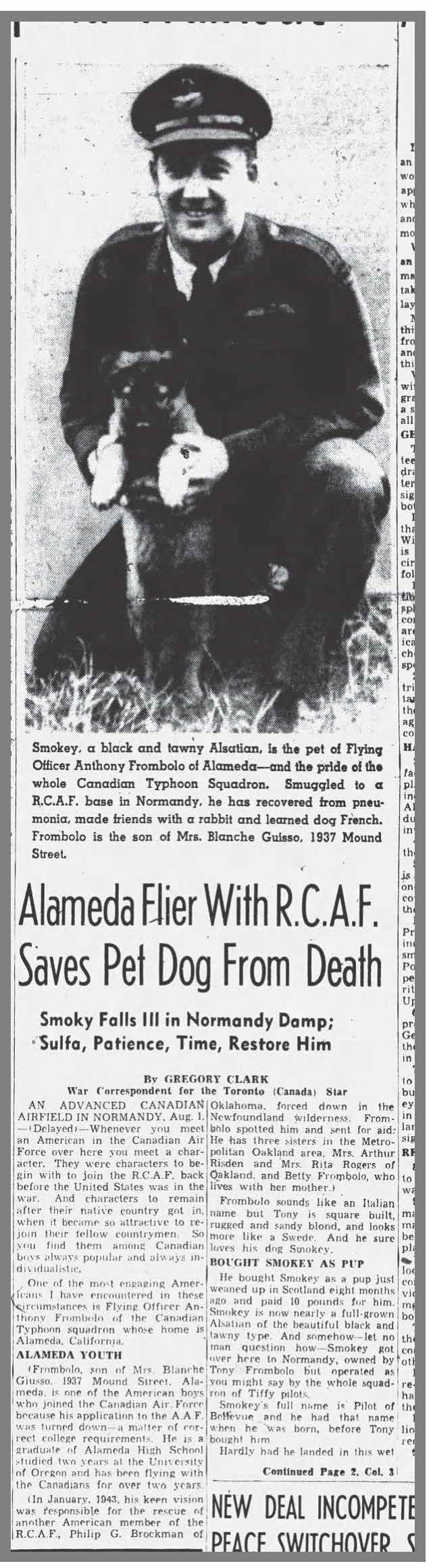

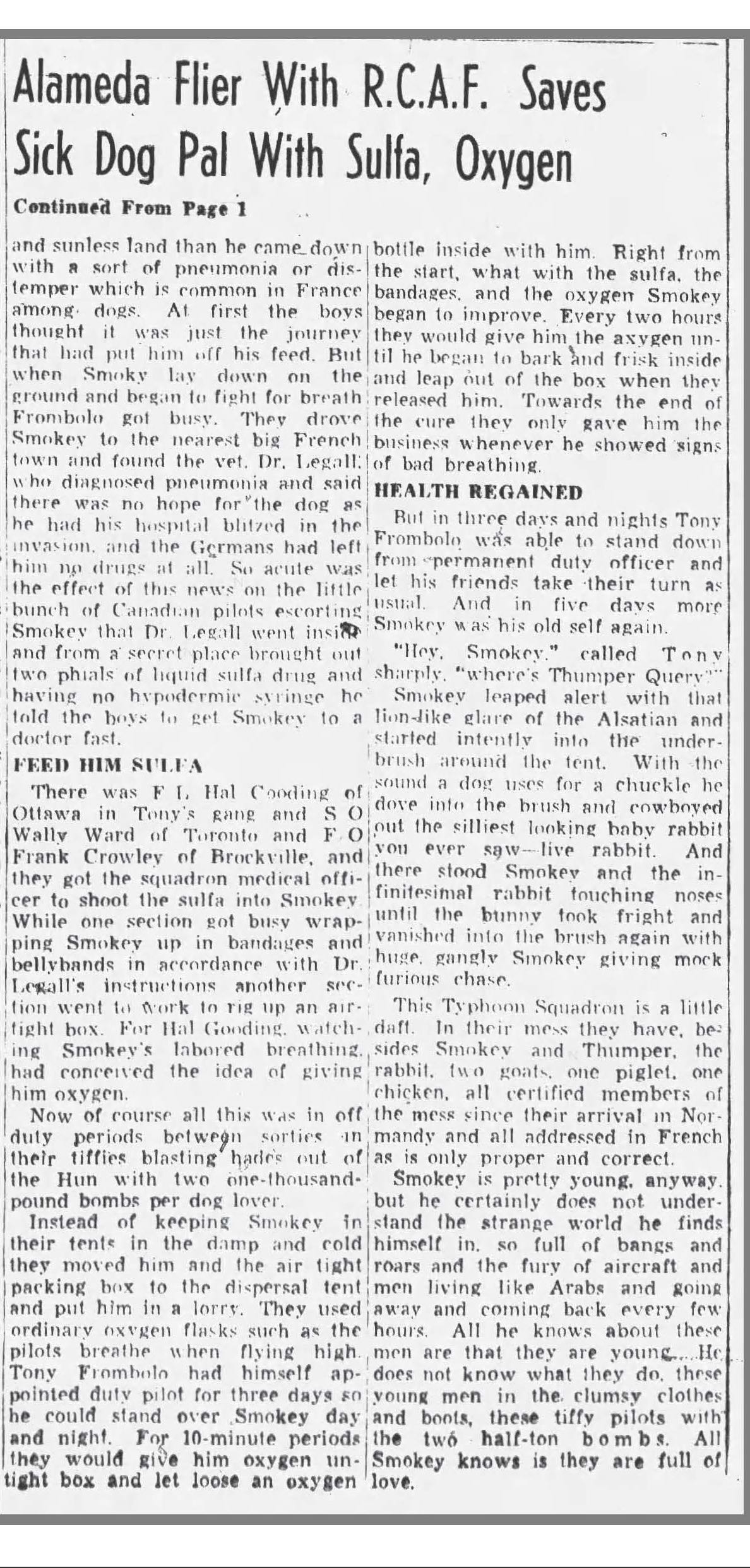

Doug Gordon, 440 Squadron said: "'Tony' we called him. He owned a dog during the war. Fairly big dog, too. Got sick and gave the dog oxygen. Tony became a POW."

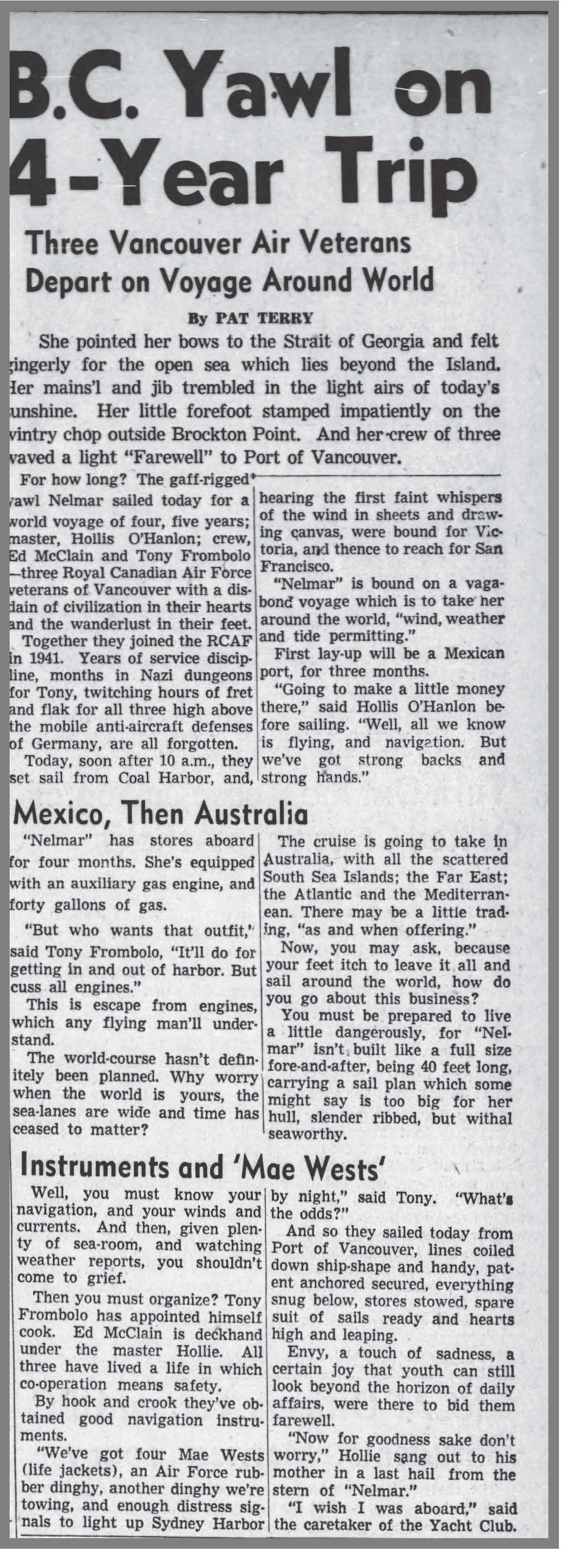

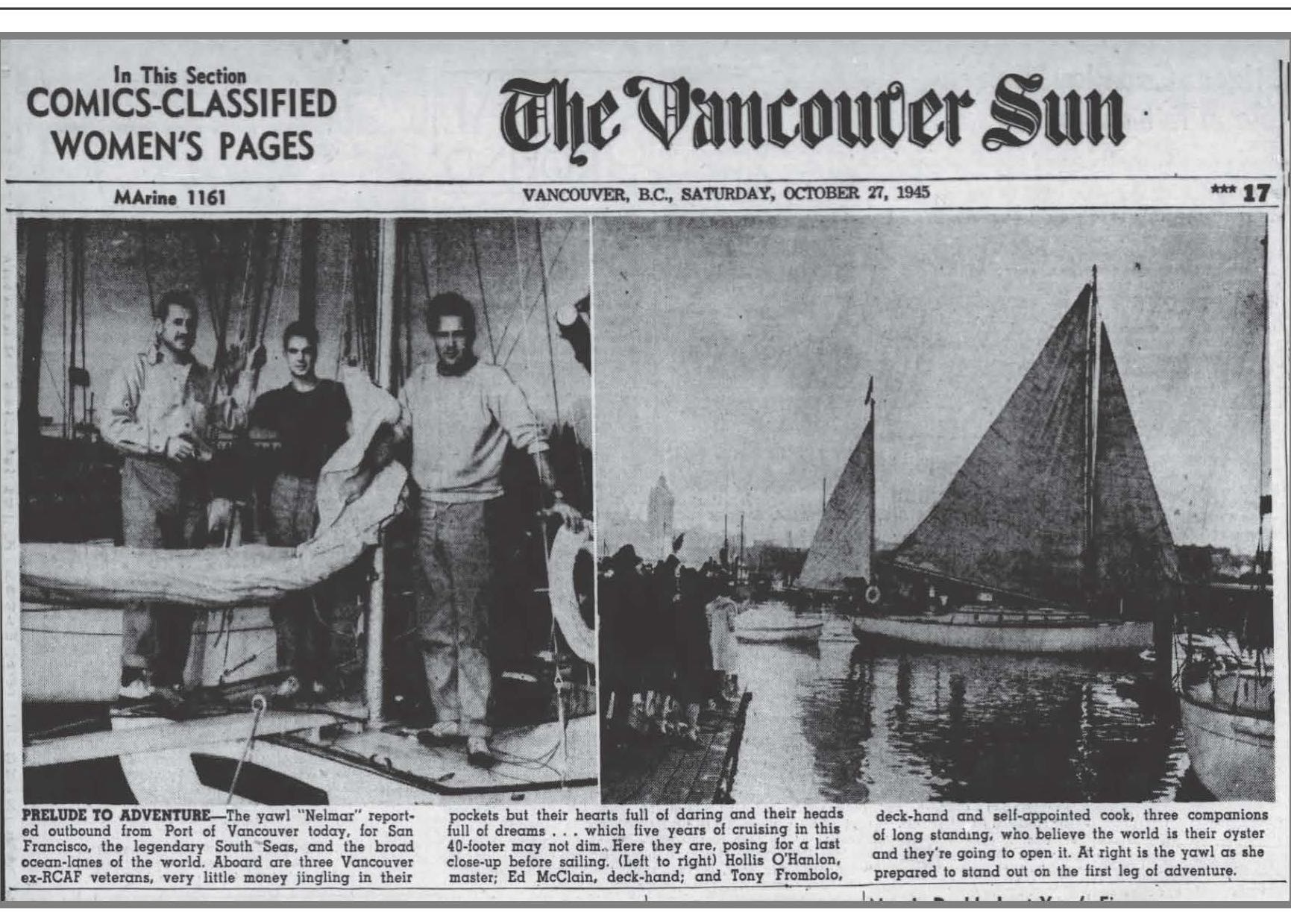

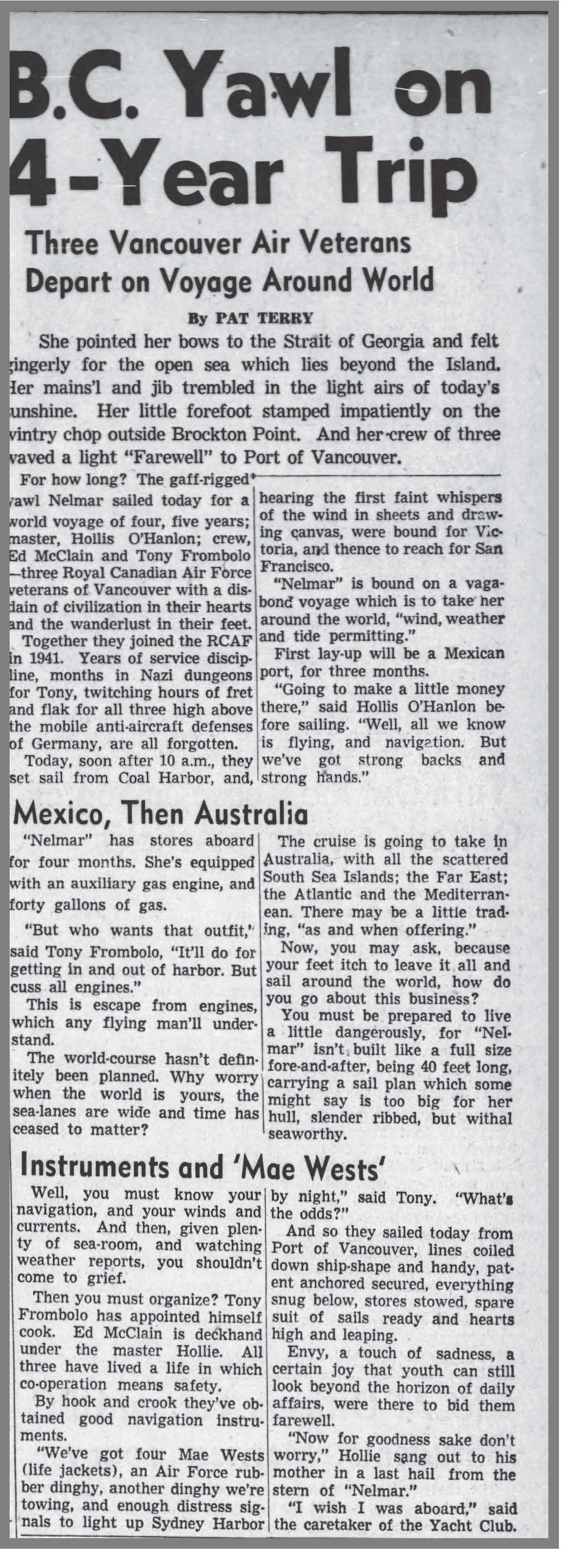

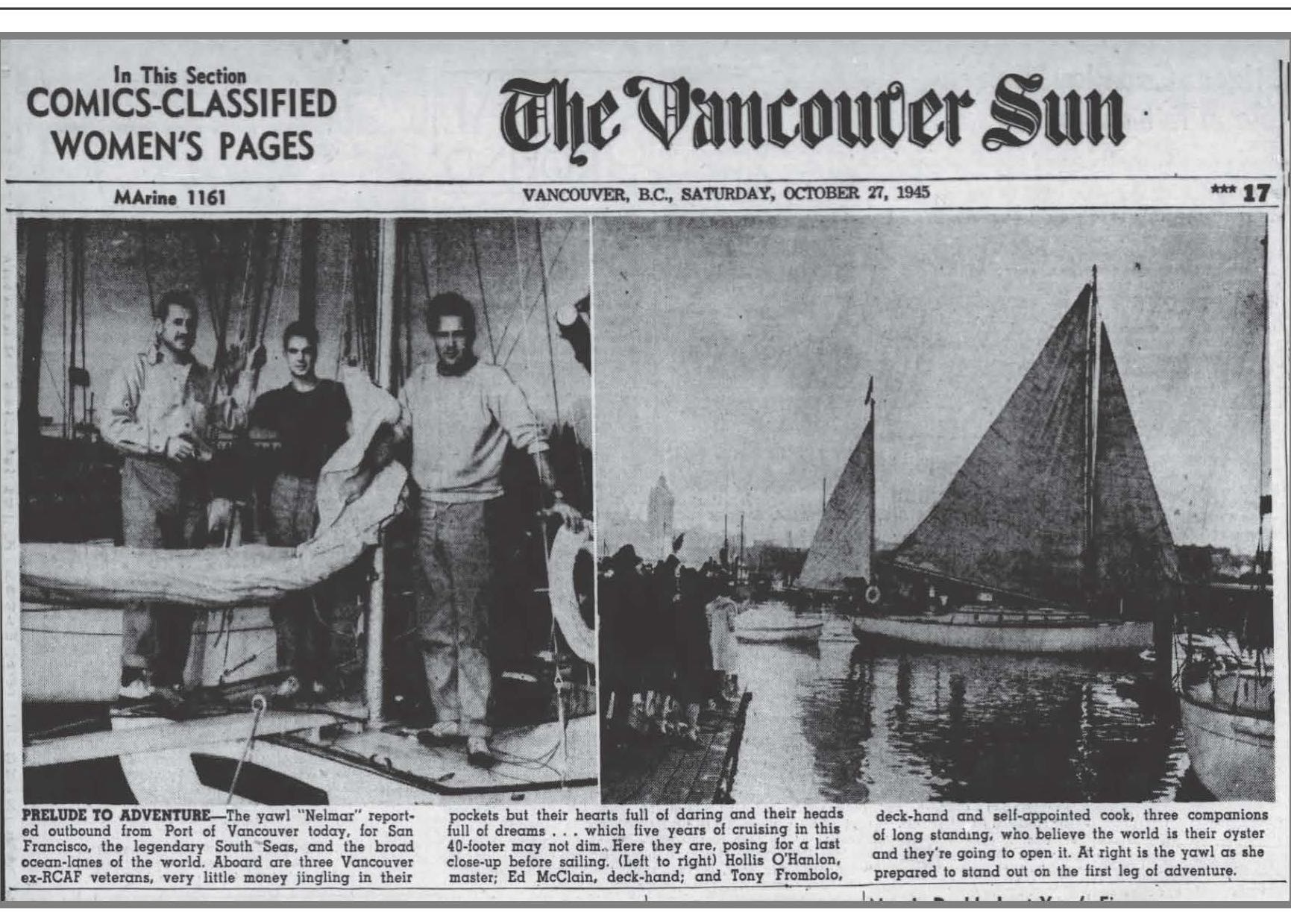

The newspaper articles above note that Tony went on a long journey, not in the skies, but on the water, after the war.

For more information about Tony Frombolo, please consult Typhoon and Tempest by Hugh Halliday.